Upzoned: Balancing Act

SF’s Family Zoning Plan has officially become law. The plan aims to weigh state housing compliance versus local concerns, but its impact on affordability — and existing tenants’ rights — remains to be seen.

This is the third article in an ongoing series exploring San Francisco’s Family Zoning Plan, which the City claims will expand housing affordability and availability by allowing for increased density along transit and commercial corridors. View all stories in the series here.

Late December, on a 7–4 vote, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed and Mayor Daniel Lurie signed the Family Zoning Plan (FZP), a sweeping update to San Francisco’s housing rules designed to bring the City into compliance with state housing mandates by increasing development capacity in low-density neighborhoods.

As we reported last month, thoughts on the FZP vary wildly. Some consider the plan a good first and necessary step toward building more housing. Others, on the other hand, think it’s a complete sell-out of working-class San Franciscans — political posturing with little substance.

Now that the FZP is law, where does that leave us?

Zoning Ain’t Housing

The state of California has mandated that local governments zone for millions of new homes statewide by 2031 or face penalties.

Secretary–Treasurer Rudy Gonzalez of the San Francisco Building and Construction Trades Council said the council has recognized both the urgency of state deadlines and the concerns raised by labor allies. He described the FZP as an imperfect but necessary first step.

“I think we have to look at it through the lens that it’s a policy document,” Gonzalez said.

Quintin Mecke, executive director of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, views the FZP as an administrative flex rather than a meaningful strategy.

“It’s just an exercise in zoning compliance,” he said. “It’s not a plan. It’s not meant to be a plan. It’s simply submitting this for approval.”

While zoning changes can allow more housing to be built on paper, Mecke said that these changes do little to address the realities that have stalled construction, which are often put down to rising construction costs, high interest rates, and a lack of public investment.

He also characterized the zoning plan as a relatively small piece of the housing crisis and said that it would only become meaningful if paired with more ambitious policies.

“I don’t think anything’s going to happen as a result of zoning unless you pair it with really deep, innovative ideas,” Mecke said, pointing to the use of public land and stronger incentives for affordable housing. “At this point, that conversation is not happening.”

An Unfunded Mandate

Gonzalez voiced broader concerns about what he sees as an unfunded state mandate to build tens of thousands of affordable housing units without adequate public investment. Private developers, he said, cannot produce deeply affordable housing without subsidies, making public funding essential.

Housing advocates say the FZP does little to address the deeper affordability crisis without a serious commitment to funding new affordable housing.

“We may not all agree on how to do it, but if we don’t talk about funding, then we’re not going to be talking about building affordable housing,” Mecke said.

He contrasted the City’s approach with more aggressive funding strategies, including taxing wealthy residents to support housing production. He also criticized what he described as a “dated, neoliberal” reluctance to ask high-income residents to contribute more, noting that significant local wealth remains largely untapped to address public housing needs.

“There’s billions of dollars in this town,” Mecke said, “yet it’s all held in private domain, and we ask almost nothing of them.”

‘Totally Disrespectful’

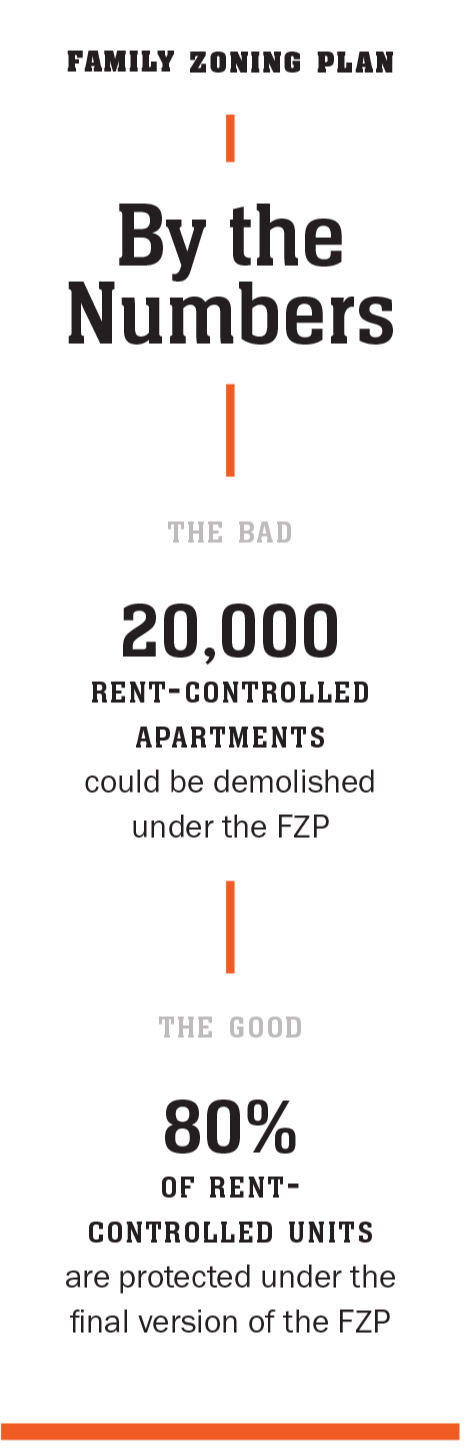

One of the biggest concerns surrounding the FZP is the potential for smaller rent-controlled properties to be demolished to make way for taller buildings with more units that won’t be rent-controlled.

Kim Tavaglione, executive director of the San Francisco Labor Council, said the vote marked a painful moment for tenants and workers across the City.

“I feel like working people were sold out,” she said. “The fact that people would just entertain possibly wiping out 20,000 rent-controlled apartments — it’s a really, really sad day for San Francisco and working people, period.”

Tavaglione said the debate revealed what she described as a lack of understanding among some supervisors about the realities facing residents simply trying to keep a roof over their heads.

“I think it showed the true colors of a lot of supervisors and was totally disrespectful,” she said.

She credited District 11 Supervisor Cheyenne Chen’s proposed tenant protections as a positive step, but said broader support was still lacking.

While the SF Labor Council opposed the plan unless it was amended, Gonzalez said the SF Building Trades ultimately concluded that passing the zoning package — with improvements — was preferable to risking noncompliance with state housing law. The final plan included protections for roughly 80% of rent-controlled units — a compromise Gonzalez credited to District 7 Supervisor Myrna Melgar’s work with housing and labor advocates.

He said that most of the rent-controlled units not covered are in one- and two-unit buildings, while larger multifamily buildings — those most vulnerable to large-scale redevelopment — were largely protected.

What’s Next

“It ain’t perfect and it ain’t pretty, but it’s here, and we better figure out how to continue to collaborate, because housing and affordability are permanent issues for labor.”

For building trades members, Gonzalez framed the decision as strategic and rooted in long-term thinking.

“We made a strategic decision to throw our weight behind the plan because we felt the urgency to move the zoning part of the discussion forward,” he said. “At the same time, we recognize that there are other leaders in the labor movement who legitimately believe that the plan falls short of the aspirations and goals that the labor movement had for it.”

Rather than holding up the plan, the trades opted to push it forward and pursue additional protections later.

Mecke said the disconnect between zoning debates and residents’ day-to-day struggles has made building public momentum difficult.

“There are so many other external things that people are worrying about,” he said. “‘Hey, have you heard about zoning?’ — and someone’s like, ‘I can barely get by in my two jobs.’”

Mecke also expressed frustration with what he described as a lack of collaboration from the mayor’s office and its allies during the process.

“It was very clear that once the mayor and his allies had made their decision, they really weren’t going to entertain other conversations,” he said.

Gonzalez said that future legislation could address unresolved issues. He also suggested the City could revisit zoning in well-resourced neighborhoods that currently face little or no upzoning, such as areas dominated by single-family homes, to offset protections for remaining rent-controlled units while maintaining overall housing capacity.

“It ain’t perfect and it ain’t pretty,” Gonzalez said, “but it’s here, and we better figure out how to continue to collaborate, because housing and affordability are permanent issues for labor.”